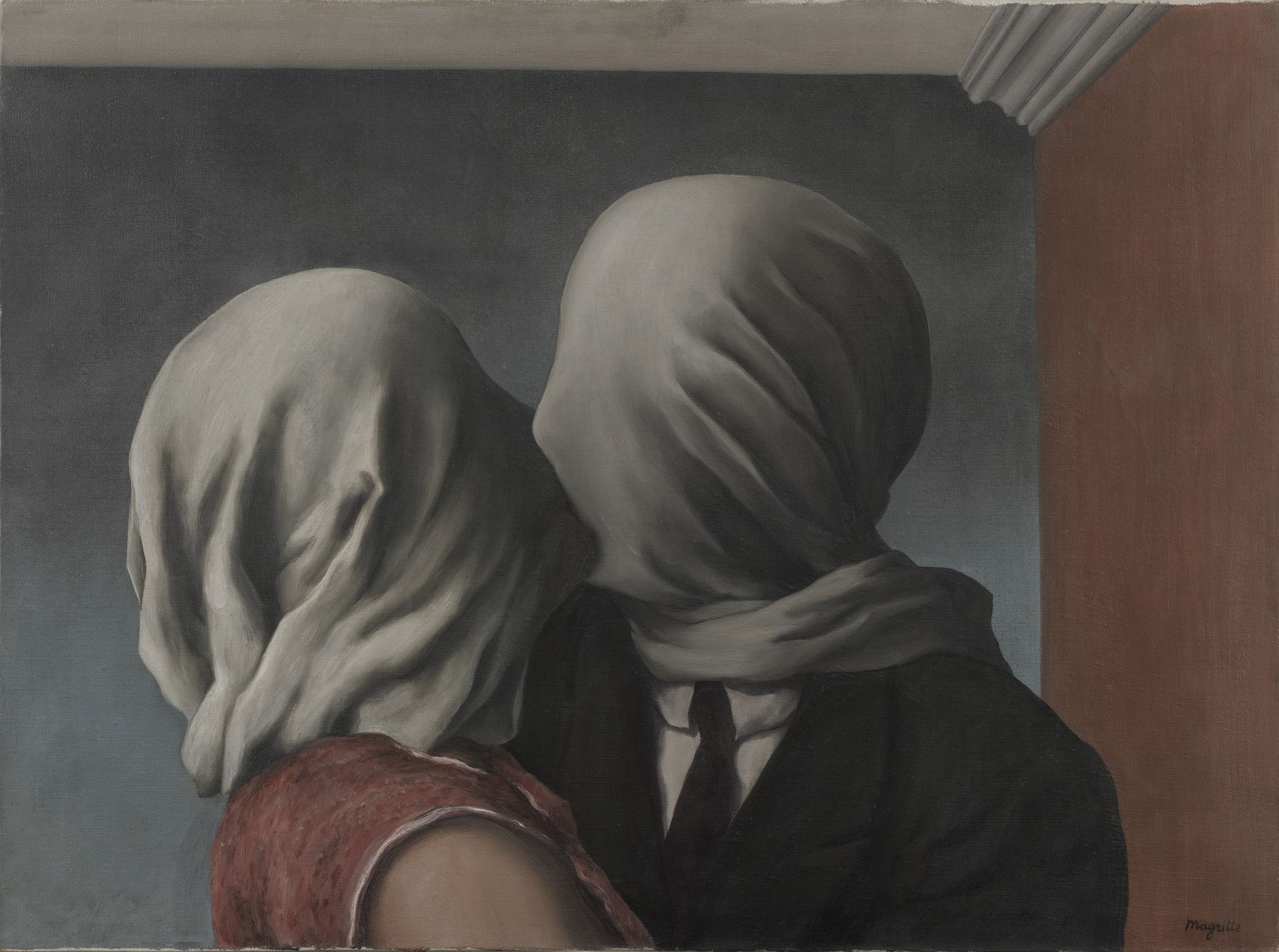

The Lovers by René Magritte, c. 1928

I slid the book out from the shelf. In it was a slip of faint chartreuse paper that read Book Corner - Bloomington, Indiana at the top. It's common to see all shades of yellowing on old receipts, but never before had I seen hues of green on thermal paper. Surely, in another eleven years, the remaining ink will be gone and the hues more vibrant.

What would a sophomore at Louisville had been doing on campus in the hoosier state? It probably had something to do with music, but there's proof that she also bought a copy of Raymond Carver's short story collection, Where I'm Calling From. That receipt, our evidence, was used to mark the start one of Carver's most famous stories: What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.

She told me that story struck her...that at nineteen years old it informed the way she thought about love. Raised in suburban Cincinnati by a pair of school teachers, she was a bright student, a gifted musician, and the recipient of a full ride scholarship. In short, she was the kind of girl who hadn't given much thought to romance before she entered the great big world. I'm sure you know the type.

Over the next few years she'd live as most college students do: study music education and work odd jobs and meet guys. Eventually, graduation came and a real job came and she started thinking about settling down. The very idea of settling down unsettled her. She leaned on a lot of feminist literature to cope. I'm sure you know the type.

A few more years pass. She's living with a boyfriend who was still working odd jobs whenever he wasn't getting stoned and playing games with his buddies. He relied on her to pay most of the bills and wasn't the charming boy of years ago. She didn't appeciate being unappreciated, so she took a job back home. I'm sure you know the type.

We'd been dating for a month or so when she showed up at my house with this book. At that point, I was coming up on the one year anniversary of divorce. So I was coming at love from a very different perspective, and she knew it: When We Talk About Love was my shit test.

Carver's story is not quite to my taste, but literally tackles the question posed in the title. Two married couples, getting around getting drunk on gin, get going on the topic of love. The narrator and his wife are bystanders, representing calm and light love. We don't hear anything about them. The other couple represent frantic love: the woman (Terri) having dealt with an ex that offed himself in the name of love and the man (Mel) a strained first marriage.

The plot thickens when Mel offers a nihilistic view of love: we have all loved before and when love is lost, we find it again elsewhere. All previous love is lucky if it becomes a memory. Mel knows it's cynical, and asks to be corrected. His wife is upset, but his point stands. Later, he says he wishes his wife would die, a sign that his past has stained itself on his memory.

You can tell a lot about someone when you hear them talk about love. Their past run-ins are especially enlightening. One cannot express a drop of resentment, even under the worst relationship disintegrations. But you can't go too far the other way. Having fond recollections of old flames doesn't sit well with new suitors.

I failed that shit test, not because I was bitter, but because I was grateful.

When I was in college, a creep of a co-worker told me about the three month rule: after a few months of dating pass, there is a go or no-go choice. Even if things are fine, if there's any doubt, you should pull the plug after three months. No need to waste anyone's time if you don't think the relationship has legs.

Although I'd confessed to my previous marriage on the second date, the topic wasn't breeched until the three month mark. That was a month or so after I'd read Carver, but at the time I'd forgotten about the ticking time bomb and never realized the book was a test. So, of course when serious conversation about my past came up, I did not give the answers she was looking for.

I am reserved, without a big network of people and vibrant social life. So when I get to know people, and let them know me, I love. That means I'm the guy who tells his friends he loves them, who would probably tell the familiar barista he loved them too if that were socially acceptable. I have tried to learn to hate to help me cope with the world, but I don't have that in me.

So, when pressed about my past, that probably came through. I have loved before, and I honor and cherish that love. Expressing any manner of indifference wouldn't be possible. Ms. Ohio didn't like that. She'd recently made her way back to god by way of one Jordan B. Peterson (you know the type). The entire concept of divorce is something she'd struggled with, just like any good Christian.

The last time I saw her we had a very awkward conversation at a community table inside a warehouse brewery. She drove me home and the tension continued. I never saw her again. She spent the next ten days chaperoning a trip at Disney World. And for nine of them, she was trying to decide: go or no go? For reasons I don't understand, she let that kill her mood for more than a week at the happiest place on the planet.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is still on my bookshelf, marked with that pale chartreuse receipt, the only keepsake from that ninety day free trial.

I was never bothered by the way that relationship ended. If anything, my lack of concern is more worrysome, given my sentimental nature. But in the years since, I have come to see the signs and symbols at play.

As the great Ricky Bobby once said, if you're not first, you're last. The Carver story brings up memories, but frames them as things to be forgotten. What do we do when we not only can't forget, but have vivid recollection of past love? What do you do when some other person is engrained in the lore of your partner? When the other's name comes up in storytime at family gatherings, where an uncle calls you by the wrong name?

We do not answer these questions. It is our natural inclination to repress them, the other becomes the one who shall not be named. But it just becomes baggage to tote through life, from apartment to apartment, from the garage to the attic, hoping that they stay zipped away in storage for good.