At the Roulette Table in Monte Carlo by Edvard Munch

I once again downloaded the Instagram mobile app on Sunday. There were some things I wanted to post, and the mobile web version isn't very good at that. I otherwise try to keep the app off my phone, because it's a black hole. I have a lot to say about Instagram, both as a business and as a cultural force. It's all over the map, so here are some thoughts:

-

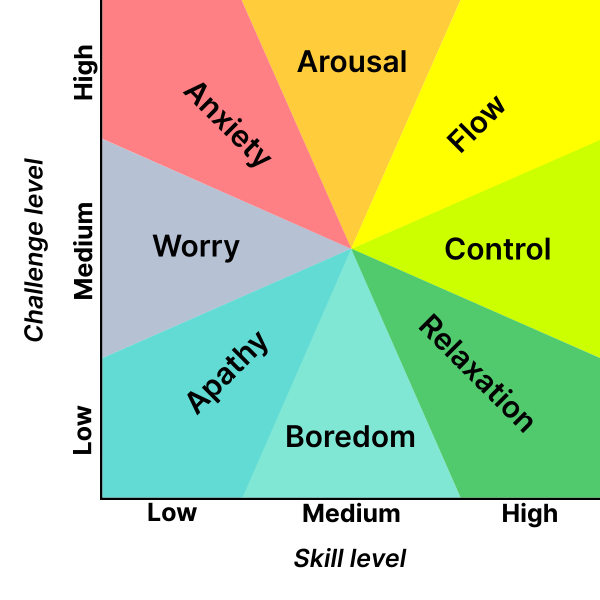

The app version is a black hole, with all it's ads and fancy full-screen casino features. The web version lacks these things, and is generally slow and painful to use, but is more respectful to attention, so I use it to keep tabs on the things I care about in between times when I want to post.

-

If it weren't for the algorithm and casino features, you'd perceive Instagram as a stale feed. This is evident to me when you switch between the app and web versions. When using the latter, it will sometimes be many days before something new shows up in the feed. The algorithm fills in those gaps so that users perceive Instagram as a fresh place instead.

-

The casino features are meant to get people invested in using Instagram. They solve the chicken-egg problem of social spaces. People need to be publishing fresh posts regularly in order to have enough to show other users.

-

People are hesitant of posting things that last, which is why Instagram added stories. When you use the web version, without the algorithm, this becomes clear: there are 100 times more stories posted than regular feed posts.

-

The Story has become it's own medium, and has transcended the low-polish ephemerality of it's origins. It's actually Instagram's most robust feature; a canvas for creating posts free of the strict constraints placed on feed posts. It's the only place where you can attach hyperlinks to posts, and there are also a wide variety of games you can attach to stories, like Q&A's, prompts, and more. It's funny that all this engineering has gone into a medium which self-destructs after 24 hours, but it works. Like I said, 100x more stories than posts.

-

If Stories are the fun thing to do with your friends, Reels is like a circus that aims to capture you and your friend's undivided attention. Again, this was another feature copied from a competitor, but I don't think Instagram explicitly did this because they thought it was in high demand. The company has tried to get video to work for the last decade. This is because video unfolds over time, and if it's good, can hold the average viewer's attention for longer than a still photograph. And Instagram is tracking every last second of video. The longer you watch something, the stronger signal you are sending to the algorithm: I'm eating this, please bring me more. Notice I said eating, not liking. There's no distinction between love-watching and hate-watching, there's just a state the algorithm looks for: that the play button is set to on.

-

It's important to note that the posts on Instagram follow a Pareto distribution. I'd say 90% of the content on the platform comes from 10% of the users. And it's not a stretch to say that Reels is probably even more exaggerated than that, maybe a 97-3 split. They're a little bit tougher to make, and require slightly more polish, but users who put in the effort are rewarded when the algorithms boost their Reels.

-

That gets me into the meat and potatoes of my observations. Reels, for the most part, is trash. Very rarely do I come across something truly entertaining, and when I do it's usually from a very creative person who's smart enough to follow established formats and patterns from TV and movie writing. The vast majority is lip synching and coked up montages and just downright dumb shit, like suburban women making countertop nachos. How the algorithm decides I should see some of these things is beyond me.

-

Before the internet, there were a handful of publishing companies and a handful of music labels and a handful of movie studios and a dozen radio stations and papers in each market and few dozen TV channels that we all watched. And all of that was guarded by gatekeepers and tastemakers, that for better or for worse, controlled the quality of programming that made it to our eyeballs. Not so on Instagram.

-

Quality aside, one of the most interesting parts of all this to me is the infinite number of algorithmic realities. There are no arbitors. Instagram and any curious anthropologists may be able to make a rough map, but there are two billion versions of Instagram. Yours is different from mine is different from your mom's. It's not like TV, where everyone watches the same handful of shows. There are millions of personalities for you to divvy out attention, and those slices of attention are so small that no even you, let alone your friends, are aware of it.

-

Still, there are regions of Instagram where a critical mass of users dwell and talk about their own little drama. Sometimes, you'll notice this drama's export into the larger cultural discourse. I think this is most evident in gender wars. The manosphere has been well covered by now. But I think it's just as bad on the girlboss side of things, but it's tough for people to talk about without going scortched Earth. I think most of this talk happens among single people, which leads to the next point.

-

I'd wager that my married friends and my mom are totally unaware of my previous point. Their algorithms show them something entirely different. I imagine my peers with kids have similar drama over parenting. I don't know what boomer algorithms are like, hopefully jolly though.

-

This sort of thing is textbook echo chambers, but I haven't really seen that talked about, I think because Instagram appears to be more about vibes than points-of-view. But I think that there are deeper pathologies behind the vibe, which are making lives much harder than they need to be.

-

The algorithm also has interesting implications on people doing Real Art. Pleasing the machines is a full-time job. You've always got to be performing for the gods, which makes deep work prohibitive. Does Real Art remain behind the gatekeepers and tastemakers?

-

The people who don't make Real Art are platformers, and tend to retread the same topics over and over. They may be moving their lips and gesturing violently, but what are they really saying? Is there anything of substance, or is this just filling time. Will people get bored of this? Or is this just a part of the standard people watch five hours of TV per day sort of thing?

-

There are many, many entry points for sub-average people to contribute to a particular machine, the meta-discourse of the machine, etc. It's hard to notice on IG sometimes, but it is evident on Youtube (not limited to Instagram), which has better search/index affordances for finding things. Everyone is hoping their 15 minutes of fame will stick around for a few years, I guess. And there's not a network exec in site to pull the plug, so they pull the slow fade.

-

Actually interesting to see theorizing on how tiktok wants to become a search engine, and also how Google is Tiktok-ifying it's search results. What do, IG?

-

This stuff is shaping us, and people aren't happy with the way they're being shaped. But there's a learned helplessness (that's often taught by the internet) that prevents people from making a change. there's also a learned sense of agency that pushes people along, using the same tactics to get people to change, but it's often too much too soon, and people fall back into helplessness.

OK, that's all...for now.