I saw a few dozen fresh faces running along the banks of the Ohio this morning. Some young and some old. Some thin and others round. You can pick these people out of the crowd: they're overdressed, breathing heavy, and are moving in ways that are sure to bring them knee pain, if it isn't already. One girl even appeared to be livestreaming the first day of her newest pursuit, something you don't really see from a habitual runner.

There's something about new year's resolutions that have always puzzled me. Like most, I've tried and failed every single time. Perhaps you make it two or three weeks, but eventually the wheels fall off and you're right back to where you were on the new year's eve.

We know, this but for some reason we still find ourselves participating in our own well-wishing. I tilt towards nihilism, and some years I swear off resolutions. How stupid, I say, to believe that this turning of the calendar will somehow bring change. But the overwhelming volume of optimism is contagious, and even if I tell myself I wouldn't, I secretly make a pact to do something, even if it won't stick.

I've come to realize that this ritual, even half-assed, is symbolic of our fight against time. We cannot, will not, roll onto our backs and let the reaper scratch our bellies with the tip of his scythe. No, today we resolve to fight back, if even for a day.

So establishing control over our lives, and therefore time, is always on our minds. I could go on and on about why we do or don't maintain that control, but I'll save the lectures on Desire for another time.

Instead, I'd like to offer some thoughts on maintaining control, something I've been grappling with for nearly thirty years.

To me, the biggest problem with resolutions is that they're framed as growth, which means that they must be quantified, like a pediactrician charting the weight of an infant or an accountant tracking the money in the bank.

This is evident in both the self-help section of your local bookstore and much of the academic research carried out by scientists. Get 1% better every day, the story goes, and you will be superhuman in just a year's time. The focus is on the destination, even in a world dominated by the platitude it's all about the journey. (Maybe this is the year you'll realize that people never mean what they say).

Just like when you tell your boss that you failed to meet your sales target or hit that production quota, the pressure builds. It feels like a lot is on the line, even though you got along fine last year while carrying that extra 20 pounds or spending 5 hours a day on TikTok. You like the idea of being in shape or spending your time doing more valuable things, but as soon as the journey gets real, you turn around and head back home to the you of years' past.

Yes, this is the nihilist in me (and probably in you, too) talking. But you didn't think I'd be here, writing an essay on new year's resolutions if I didn't at least have an ounce of hope in me?

Of course I too am sitting here, thinking what needs to change, because I am stubborn and will not let Father Time do me dirty. Nope, not this year brother.

My stubbornness makes life a real challenge, but it comes in handy, because I refuse to give in to entropy, to continue doing things even though I know they don't work. I've failed enough to know how and why I've failed, so here are a few tricks up my sleeve for this year.

Don't make public proclamations of your resolution.

It seems like if other people know, you'll feel some sort of obligation or accountability for your resolution. Newsflash: nobody really cares.

People close to you want the best for you, but they 1) have their own stuff to deal with, and 2) don't really have the spine to hold you accountable even if they had the time. You're going to have to muster up enough Will to stick to your guns, all by yourself.

It's also good to keep your resolutions private because you can recalibrate without shame. Perhaps one of the biggest reasons for quitting on your new habits is the realization that your goal was too lofty, and it's easier on our psyches to give up entirely instead of admitting that we aren't as good as we thought. And remember: nobody cares anyways.

If all goes well, you let the Work you resolved to do speak for itself. Maybe by 2024, you've lost fifteen pounds (instead of twenty) but put on some muscle mass, or become a scholar of medievalism after reading Feudal Society when you simply set out to read fifty books.

Incorporate margins of error

I really, really don't like quantifying things, but this year I'm going to try to be smart about it. I've got a few goals in mind which require me to try to practice some habit at a particular cadence. But there are 365 days in a year and 52 weeks. Life happens: you get sick, go on vacation, and otherwise prioritize other things.

I have several goals in mind (I'm not going to tell you, see above) which require daily effort. I've done this before, and as soon as I miss a day or two I give up. Not this time.

Instead, I'm going to give myself some slack by creating goals that along the lines of 95% of days I will do X and do Y during 75% of weeks. Knowing that I have free days and weeks to burn should prevent me from churning from these habits.

Make the buy-in low, with room to raise

In addition to margins of error, you can set the barrier to entry laughably low, knowing that some days you'll barely have the energy to satisfy the requirement but many days you'll have the energy to triple the work. Basically, just show up to work most days, and eventually you'll get things done. If you're struggling to even be there, perhaps this thing wasn't all that important and you should recalibrate, or maybe quit having learned that you liked the idea more than the practice.

In practice, I'm probably going to use some sort of color-coded calendar, where a blank day or week means you didn't do it, a yellow square means I did just enough, and green, blue or other colors indicate I doubled and tripled the bar today.

Over time, I've developed the understanding that the creation of goals is mostly about building a sustainable routine. You shouldn't aim to be high-achieving because that's really hard to do, and even hard to continue doing over the course of years and decades. Instead, resolutions should be intended to make the average Tuesday in 2028 more enjoyable than it was in 2018.

Can you set yourself up to feel less pain and more energized, to feel more in touch with your soul, to feel more connected to the world around you? At the end of the day, that's what goals around fitness, spirituality, and family are trying to address. If you can make space for full days, and figure out how to manage them over months, years, and decades, I think you'll be much more satisfied with the life you've lived than if you'd set huge goals and fail.

I'd like to write some more, but I tend to ramble on and struggle putting a bow around my thoughts. So I'm going to give you this hastily wrapped box and resolve to fix this bad habit (😉).

Happy new year. Love, Bryan.

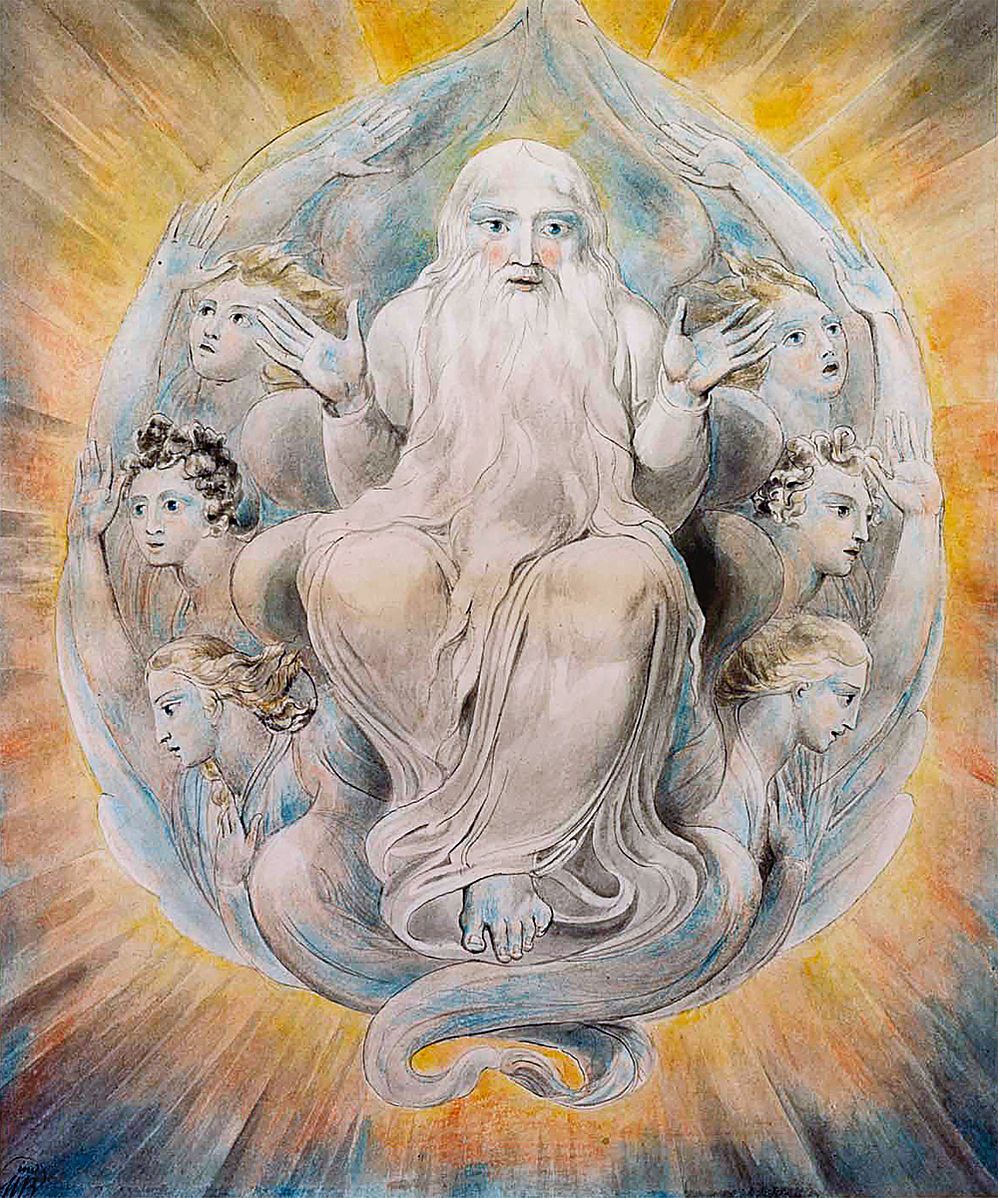

You might be wondering, "What's the deal with the peacock?"

As I often do, I was reading the wiki page for new years resolutions, and medieval tradition involved something called Vow of the Peacock, which was an opportunity for people to state their commitment to chivalric values. I thought this was fun, and I had to pull myself out of that rabbit hole to press publish here. But, rest assured, no peacocks were harmed in the creation of this essay.